Sample lidR Workshop

About this Document

Below is a sample of a potential workshop I began writing as an introduction to working with LiDAR data in R. While this was never presented, it was a way for me to document and save a sample of the code I was writing as I worked through processing a LiDAR dataset. Rather than completing these steps in GIS-specific programs that I was familiar with, I used these data as my introduction to the use of R for spatial analyses. It now mostly functions as a way to share a project that I began working on in early 2019. It has been updated to reflect changes and additions through updates of the lidR package.

Load Packages

The first thing we will want to do is set the working directory and load our packages. Note that loading lidR will also automatically load “raster” and “sp”—two packages that help visualize and process spatial data. rgdal is another one that helps deal with spatial data, we will use it to export our trees. Loading lidR will also load sp and something else that are both important to do stuff.

Check the working directory and make sure it is set to where your data is! This is always the first step and am important part of data management.

getwd()

FALSE [1] "/Users/jordanellison/Desktop/lidarpubstuff/working"

library(raster)

## Loading required package: sp

library(rgdal)

## rgdal: version: 1.5-16, (SVN revision 1050)

## Geospatial Data Abstraction Library extensions to R successfully loaded

## Loaded GDAL runtime: GDAL 3.1.1, released 2020/06/22

## Path to GDAL shared files: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/library/rgdal/gdal

## GDAL binary built with GEOS: TRUE

## Loaded PROJ runtime: Rel. 6.3.1, February 10th, 2020, [PJ_VERSION: 631]

## Path to PROJ shared files: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/library/rgdal/proj

## Linking to sp version:1.4-2

## To mute warnings of possible GDAL/OSR exportToProj4() degradation,

## use options("rgdal_show_exportToProj4_warnings"="none") before loading rgdal.

library(sp)

library(lidR)

Next we will load our lidar data, clip it to a smaller sample area, and plot it. Find the las file that should be saved in a folder within the directory. We’ll bring in our las file and clip it to a much smaller extent. This will make things a bit easier to work with as functions for example will run a lot faster.

Import Data

The las file we’ll be using today was downloaded off the USGS National Map with data from the 3D Elevation Program. Click these links to learn more about the 3DEP program or search for data relevant to you!

This las file are tiles from Central Colorado. It is projected to NAD83, UTM 13N so the unit of coordinates and elevation values are meters. Note that I changed/reprojected the dataset to be in accordance with other data we have, hence the name “projected.las”

las <- readLAS("data/projected.las")

## Warning: There are 5095 points flagged 'withheld'.

Next, we can clip the point cloud using coordinates of a sample bounding box.

las <- clip_rectangle(las, 495500, 4332500, 495550, 4332550)

plot(las)

With lidR, the plot function will open a window that allows you to zoom and pan through your data! Pretty neat!

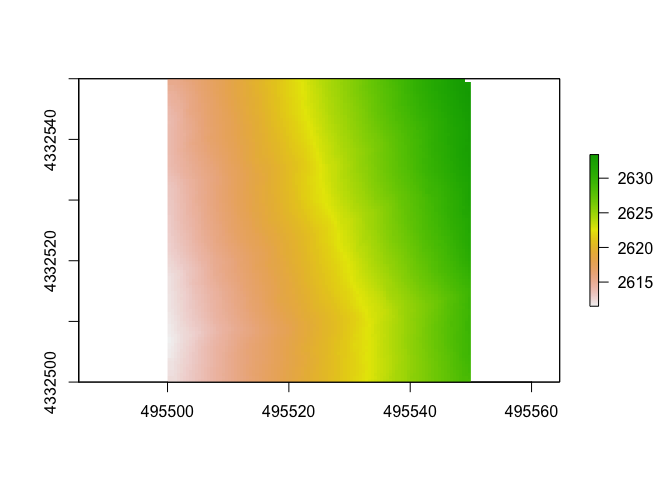

Make a DTM

Next, we will make a DTM, or digital terrain model. This is a type of DEM (digital elevation model) that will be generated from only points classified as “ground” within the point cloud. Let’s set the resolution to 0.5m.

There are different algorithms used to do this, but we will pick just the classic “tin” where our output is an interpolation from a Delaunay triangulation and extrapolated from nearest neighbors. The command “grid_terrain” can also use other spatial interpolation algorthims such as a point to raster (p2r), kriging (kriging) or k-nearest neighbor (knnidw). For each of these algorithms, there are default parameters but you have the ability to adjust and set your own within each arguments.

Here we will set the resolution to 0.5 cell sizes(they’re in meters as that’s the unit of our data), but feel free to select adjust as necessary, depending on the density of your point clouds. You can use the argument grid_density(las, res = 0.5) to get a map of the point density.

dtm1 <- grid_terrain(las, res = 0.5, algorithm = tin())

plot(dtm1)

Make a CHM

To make a CHM, or canopy height model, we will first “normalize” the dataset. The normalize_height() command will subtract the DTM we just made from the lidar point cloud. This will effectively remove topography and ground will be set to 0. Don’t worry the original z values will be kept and stored in a new attribute (“Zref”) in case you’d like to go back to original elevations. You can also use the command unnormalize_height() to do this automatically.Now, z values will reflect the distance from the ground rather than elevation above sea level. This will be useful for determining tree heights from the CHM we create, as now it can be done directly from the point cloud. There is also an alternate way to do this, skipping over creating a DTM object, and combing the steps. That code might look like:

las <- normalize_height(las, dtm1) ##first method

las1 <- normalize_height(las, tin()) ##alternate method

Note that that I separated the objects- this is so that you can try looking for differences between the two methods.

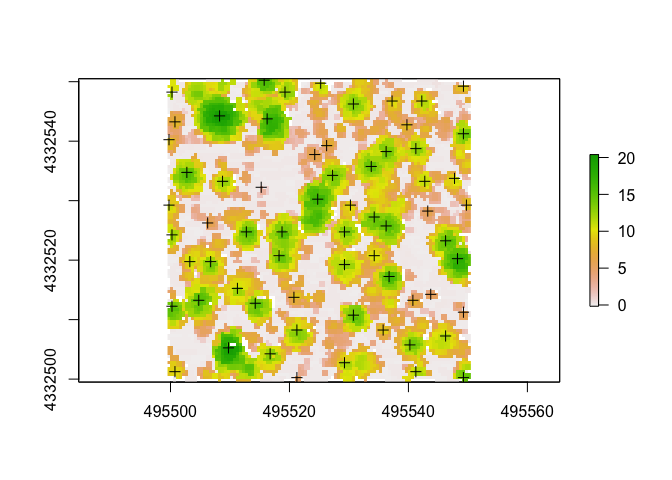

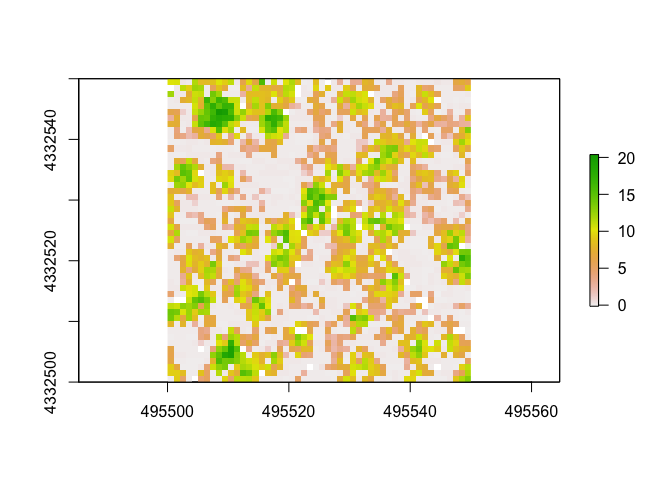

Once the point cloud is normalized, we will can try two different methods to get the CHM. The first will use point densities and the second will use a similar method of triangulation that we used to generate the DTM.

chm <- grid_canopy(las, res = 0.5, p2r(0.3))

chm1 <- grid_canopy(las, res = 0.5, dsmtin())

Now let’s look at plot the chm using the point to raster method.

And now the chm created using a TIN method.

rplot(chm1)

How these look different?

Another way to look at tree heights is by looking the histograms. With the base hist() function, we can look at the distribution of heights above ground across the rasters.

Point to raster chm:

TIN chm:

So, can you see any differences between the different algorithms used to calculate the CHM?

Notice that the first one generated many points below 0!!! This is a big red flag!

Tree Segmentation

There are a two approaches people take to doing this, with the CHM or directly from the point cloud. For each of those two methods, there are multiple algorithms and methods to do it. In lidR, segment_trees will return a point cloud with trees segmented regardless of method/algorithm used. Today we will generate trees from within the point cloud, again naming the object the same as the file to just add a new field of ‘treeID’ rather than taking up precious space and making a new point cloud.

From the Point Cloud

There are various methods to segment trees using the lidR package. This method below for example was adapted from Li et al. 2012 1.

Note that you can modify the name of the attribute and how the ID number is generated (here I show the defaults). Modifying the “uniqueness” is most relevant when working with several tiles/chunks of point clouds. See ?segment_trees for more details.

las <- segment_trees(las, li2012(), attribute = "treeID", uniqueness = "incremental")

From the CHM

Another way is to use the CHM. We can detect the tops of the trees and use it in conjuction with the CHM to determine where trees are. First we’ll pull out the tree tops. With this, we can also adjust the size of our moving window (here I use “4”) and the minimum height. Note that a function can be written and used in place of a number for window size.

ttops <- find_trees(chm, lmf(4, hmin = 2))

plot(chm)

plot(ttops, add=TRUE) ##plot the CHM and tree tops

Do the tree tops (+ on plot) seemingly match up with what we can visually parse out as trees from the CHM?

Now that we have the tops of tree identified, we can use a method adapted from Dalponte and Coomes 2016 2.

#las <- lastrees(las, dalponte2016(chm, ttops)) ##note that it was not run

Finally, inside the lidR package, there are a few other algorithms that you can use such as silva2016() or watershed() that also use rasters.

I highly recommend diving deeper into each method to determine which is appropriate for your data.

Raster From Point Heights

Another way we can generate a DTM is by using the 95th percentile of heights of points. We will first calculated a set of standard metrics (although you can customize and calculate your own) and then subset the data. The standard

metrics1 <- voxel_metrics(las, .stdmetrics_z, res=1)

summary(metrics1$zmean)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## -0.150 0.035 5.982 5.767 9.660 20.250

summary(metrics1$zsd)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

## 0.000 0.014 0.055 0.106 0.140 0.693 3207

summary(metrics1$zentropy)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

## 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0448 0.0000 0.6309 2148

As you can see, there are a variety of metrics that can be automatically calculated. You can also write your own functions to use to calculate specific metrics you may be interested in. Below is how to calculated the canopy height model using the 95th percentile Z heights. I’ve seen this done in at least one forest service technical report, but don’t have a specific example to cite.

xy1 <- subset(metrics1[,1:2]) ##subset xy coords

z95 <- subset(metrics1[,30]) ##subset z coords

xyz1 <- cbind(xy1, z95) ##combine xyz coords

raster1 <- rasterFromXYZ(xyz1, res = c(1, 1), crs = "+proj=utm +zone=13 +datum=NAD83")

plot(raster1)

Other Functions

There are a bunch of other cool things one can calculate and analyze using these data. Here I’ll share a couple that I thought were cool/interesting/potentially very valuable!

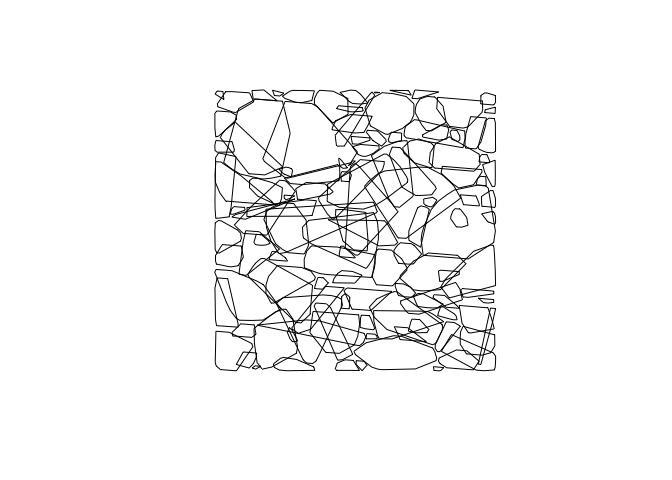

Tree Area/Volume

To calculate the area and volume of individual trees we have segmented, we will used a function that calculates delineated the crown of each segmented tree and calculates the hull of the tree. In lidR, there are 3 options for method used to calculate this: convex, concave, or bounding box (bbox). The default will be convex. If you select concave, you can specify concavity and a threshold for lengths of each segment. You can leave the “attribute” argument as the deafult (attribute = “treeID”) as this is the name of the field we used when we segmented trees.

Also note: if you’d like to calculate tree hulls using the concave formula, you must download and turn on the “concaveman” package.

convex_hulls <- delineate_crowns(las, type = c("convex")) ##calculate area of tree

bbox_hulls <- delineate_crowns(las, type = c("bbox")) ##alternate method

plot(convex_hulls) ##plot tree area

Here the plot above shows the convex hulls of the trees, but as viewed from above and only in 2D. This object convex_hulls does include stored within it the calculated area of the generated polygons.

Rumple Index

The rumple index is a metric used to calculate the “roughness” of the surface of an area by calculating the ratio of the area and the projected area of the ground. Rumple index has been used as a way to look at structural complexness/heterogeneity. Higher values of this index have been shown (in correlation with other metrics) to be associated to old-growth forests, see Kane et al. (2010) 3 or check out an application of it in Jenkins et al. (2019) 4.

According to help("rumple_index"):

“Computes the roughness of a surface as the ratio between its area and its projected area on the ground. If the input is a gridded object (lasmetric or raster) the function computes the surfaces using Jenness’s algorithm (see references). If the input is a point cloud the function uses a Delaunay triangulation of the points and computes the area of each triangle.”

Here we will use a CHM we generated earlier as the input. This means the function will use the algorithm derived from Jenness 20045.

rumple_index(chm1)

## [1] 4.184629

##Reclassify a Raster

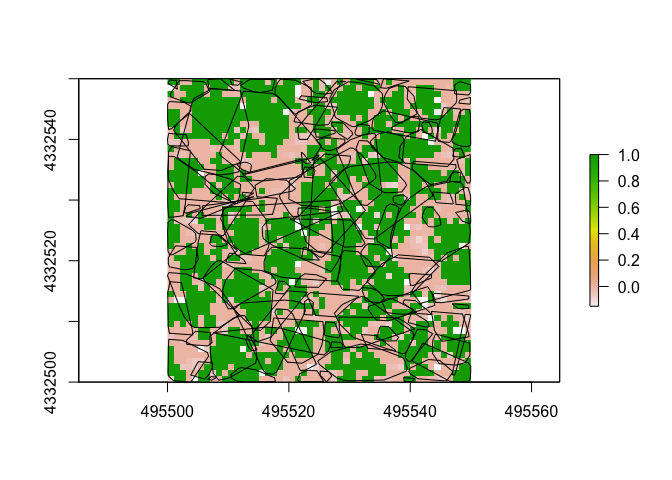

Reclassifying rasters can be a useful tool in the toolbox. Here we’ll use our CHM raster from above and reclassify it so that all values above 2m are considered potentially part of a tree. First we will create parameters (here named p) that translates to: values > 0 but < 2 become 0, while values >2 and <20.5 become 1.

p <- c(0, 2, 0, 2, 20.5, 1)

treenotree <- reclassify(raster1, p)

plot(treenotree)

plot(convex_hulls, add=TRUE) ##check it with the tree convex hulls

Conclusion

Thanks for checking out this little document I’ve put together. Feel free to let me know if you have any questions (email and twitter are on my site)

-

Li, W., Guo, Q., Jakubowski, M. K., & Kelly, M. (2012). A new method for segmenting individual trees from the lidar point cloud. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 78(1), 75-84. ↩

-

Dalponte, M. and Coomes, D. A. (2016), Tree-centric mapping of forest carbon density from airborne laser scanning and hyperspectral data. Methods Ecol Evol, 7: 1236–1245. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12575. ↩

-

Kane, V. R., McGaughey, R. J., Bakker, J. D., Gersonde, R. F., Lutz, J. A., & Franklin, J. F. (2010). Comparisons between field-and LiDAR-based measures of stand structural complexity. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 40(4), 761-773. ↩

-

Jenkins, J. M., Lesmeister, D. B., Wiens, J. D., Kane, J. T., Kane, V. R., & Verschuyl, J. (2019). Three-dimensional partitioning of resources by congeneric forest predators with recent sympatry. Scientific reports, 9(1), 1-10. ↩

-

Jenness, J. S. (2004). Calculating landscape surface area from digital elevation models. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 32(3), 829–839. ↩